A study in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer finds that vaccination in a clinically relevant genetic cancer mouse model generated a population of functional progenitor tumour-specific CD8 T cells (TST) and halted cancer progression, in contrast to immune checkpoint blockade (IBT) therapies. The authors hope that immunisation could be the “most effective strategy” for patients with early cancers or at high risk of cancer recurrence. This study takes a different approach to many cancer vaccine studies, which tend to focus on patients with advanced tumours.

Cancer vaccine potential

The authors recognise the transformational role of immunotherapies in the cancer treatment landscape, particularly in the case of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). However, vaccines for non-viral cancers have had “more limited success”. Many studies on tumour-specific CD8 T cell (TST) vaccine responses are conducted in the established/late tumour setting, so less is known about how TST “respond and differentiate” in response to immunotherapy during early stages of tumorigenesis.

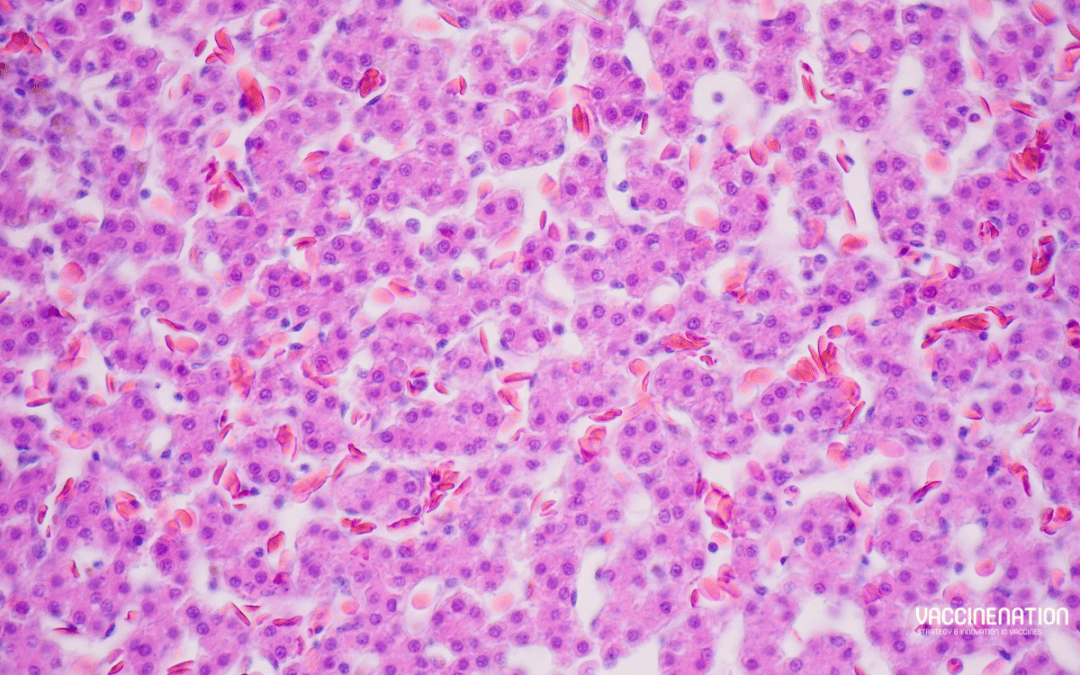

Previously, the authors developed an autochthonous mouse model of liver cancer (AST;Cre-ERT2) to initiate liver carcinogenesis with tamoxifen (TAM)-induced Cre-mediated SV40 large T antigen (TAG) expression in hepatocytes. TAG functions as an oncogene and a tumour-specific neoantigen recognised by CD8 T cells, so the model enables “precise temporal control” of the duration of TST interactions with transformed hepatocytes and tumours. In contrast to human tumours, which “arise sporadically and progress clonally”, TAM-induced oncogene induction is “highly efficient”, resulting in high antigen burden even at early stages.

The study

The researchers allowed AST;Cre-ERT2 mice to undergo stochastic TAG oncogene activation through sporadic, TAM-independent Cre-mediated activity. To explore TST responses against TAG-driven tumours they used congenic donor lymphocytes from transgenic mice, in which CD8 T cells express a single T cell receptor (TCR) specific for TAG epitope-I (TCRTAG). They found that TST became dysfunctional in TAM-treated AST;Cre-ERT2 mice and were “unable to halt tumour progression”. TAM-treated AST;Cre-ERT2 mice had a “substantial” tumour antigen burden, even at early stages of tumorigenesis.

To compare initial TST differentiation in mice with early liver lesions against those with late liver lesions, the researchers transferred CFSE-labelled naïve TCRTAG into early and late time point AST;Cre-ERT2 mice. TCRTAG in mice with early lesions divided at a slower rate, particularly in the spleen and ldLN, and there were fewer TCRTAG in the spleens, ldLN, and livers of early mice. Decreased TST proliferation in mice with early lesions could be due to the lower TAG antigen burden. Although nearly all TCRTAG in mice with late lesions and most in mice with early lesions failed to produce effector cytokines TNFα and IFNγ within 60 hours of transfer, a population of TCRTAG in were identified in the spleen and liver of mice with early lesions. These could produce effector cytokines TNFα and IFNγ.

“Thus, in hosts with sporadic early lesions, a subset of TST resisted rapid differentiation to the dysfunctional state, raising the possibility that this subset might be amenable to immunotherapeutic reprogramming/rescue.”

To see if this functional TST subset persisted, the authors examined TCRTAG immunophenotype and function 5 days and 21 days post-transfer into early or late AST;Cre-ERT2 mice. While fewer TCRTAG were found in mice with early lesions compared to late lesions at 5 days, the difference became less pronounced at 21 days. In both groups TCRTAG upregulated CD44, which indicates antigen exposure and activation. TCRTAG in early mice continued to express higher levels of PD1 than naïve TCRTAG, suggesting that PD1 expression can identify tumour-reactive TST in hosts with early lesions.

The next consideration was if the functional TST subset in mice with early lesions could be harnessed to stop tumour progression. LM, a gram-positive intracellular bacterium, induces strong CD4 and CD8 T cell responses. The researchers used an actA inIB deficient attenuated LM vaccination strain to test if early vaccination of AST;Cre-ERT2 would protect mice against liver cancer progression. Mice were either left untreated, given a single dose of empty LM, or vaccinated with a single dose of LM- TAG.

“LM- TAG–immunisation conferred a major survival advantage, with all mice remaining tumour-free and one mouse euthanised for dermatitis without any evidence of liver tumours.”

The mice in untreated and empty LM groups reached endpoint with “multiple” large liver tumours and increased liver weight. At endpoint, most TCRTAG in the LM- TAG–immunised made effector cytokines, in contrast to the TCRTAG in tumour-bearing mice in the other groups, which were “largely unable to produce effector cytokines”.

Vaccination vs ICB

“An important and open question in cancer immunotherapy is how ICB versus vaccination compares in boosting anticancer immune responses, and how best to combine and sequence these therapies.”

A comparison of ICB, LMTAG vaccination, and combined ICB/LMTAG vaccination found that ICB conferred no benefit in comparison with isotype control antibodies (iso). By contrast, LMTAG and ICB/LMTAG treated mice had no evidence of tumour progression at 400+ days. Furthermore, LMTAG vaccination, whether alone or in combination, led to a “substantial increase” in TST numbers and IFNγ production, while ICB alone had “little impact”.

LM-based vaccines have had “poor or mixed results” in clinical trials, often with a target of patients with advanced or refractory cancers. The authors hope that their studies offer “mechanistic insight” as to why these fail in patients with advanced cancers: “for vaccines to be effective, a progenitor TST population must be present”. Although the apparent superiority of vaccination over ICB “may be surprising at first glance”, the authors highlight an important point, that “not all TCF1+TST are functional, nor does ICB alone lead to functional TST”. However, the findings suggest that LMTAG vaccination maintains or rescues functional progenitor TCF1+TST.

Timing is important

Dr Mary Philip, associate director of the Vanderbilt Institute for Infection, Immunology, and Inflammation, commented that the study “suggests that the timing of vaccination is important”.

“A unique feature of our study is that these mice are at high, essentially 100% risk of developing cancers, so the fact that a single immunisation at the right time can give lifelong protection is pretty striking.”

Dr Philip reflected that very few studies follow mice “so long after vaccination” and find them tumour free for two years.

“ICB works by taking the brakes off T cells, but if the T cells have never been properly activated, they are like cars without gas, and ICB doesn’t work. The vaccination boosts the T cells into a functional state so that they can eliminate early cancer cells.”

For more progress updates from cancer vaccine researchers at the Congress in Barcelona this month, get your tickets to join us here. Don’t forget to subscribe to our weekly newsletters here.